Stutt’s final trailer ride

As Remembrance approaches, Pat Waby looks back at Stutt’s final journey.

In 1965, old Stutt and I (ed. we think he was called Stutt because he kept stoats or ‘stutts’ in Norfolk dialect. His real name was Fred). Anyway he and I had been hoeing beet until a deluge forced us to back into a hedge, corn sacks over our heads and knees. Sitting there with bottles of cold tea and sandwiches at the ready, we were content for a while.

Out of the silence Stutt turned to me and said, ‘When I’m dead ole partner, will you drive me to the church on a tractor and trailer?’

Follow that, I thought. What can you say?

I said, ‘Well Stutt, as long as the Guv’nor says w can use the trailer, I’ll be happy to drive you there.’

Now he didn’t look like he was going to peg out for a few years so I thought this will probably be forgotten.

Not so matey! About fourteen years later, his son turned up at my door. There was no ‘Good evening Pat’, or ‘Are you alright mate’, straight out he said, ‘Thass in dad’s will that you would take him to the church on a trailer, are you going to then?’

Of course’ I said, but quickly added ‘so long as the Gov’nor will loan us the trailer.’

Next morning the Guv’nor came into my workshop where we discussed the days plans, but before we got going on the day’s work, I told the story of Stutt’s request. ‘And why not!’ he said. And so I would carry out Stutt’s request.

I had some repairs to do to the trailer and wanted to fix batons around where the coffin would rest. Finally, on the day of the funeral. I drove to Cawston to pick up Stutt for his last ride on a farm trailer.

The bearers placed Stutt on the trailer inside the batons, and it was a tight fit. Then I climbed out of the back window of the tractor, onto the trailer, and taking a large Union Jack out of my coat, draped it round the coffin and pinned it down. Then I stood to attention and saluted Stutt.

We duly arrived at the church to find that the coffin had settled into the batons and the bearers couldn’t lift him off. ‘Don’t panic,’ I said, and promptly pulled the hydraulic lever to raise the headboard two foot high. The bearers looked worried now .

I climbed onto the trailer, folded up the flag and lifted the coffin over the edge of the batons and slid Stutt down to the bearers. Stutt was lifted down from the trailer one last time and carried into the church.

My old friend had his wish.

Harvest in the 1950s

As the harvest in Norfolk draws to a close, Pat Waby writes about the harvests he first worked in the 1950s

Harvest in the late 1950s was a miniature version of the 2020s. A binder was used cut the corn and put into stooks to be gathered by hand with pitch-forks and made into stacks, and when it was perfectly dry, a threshing machine would be hired and lots of labour would be used to get it into the barns.

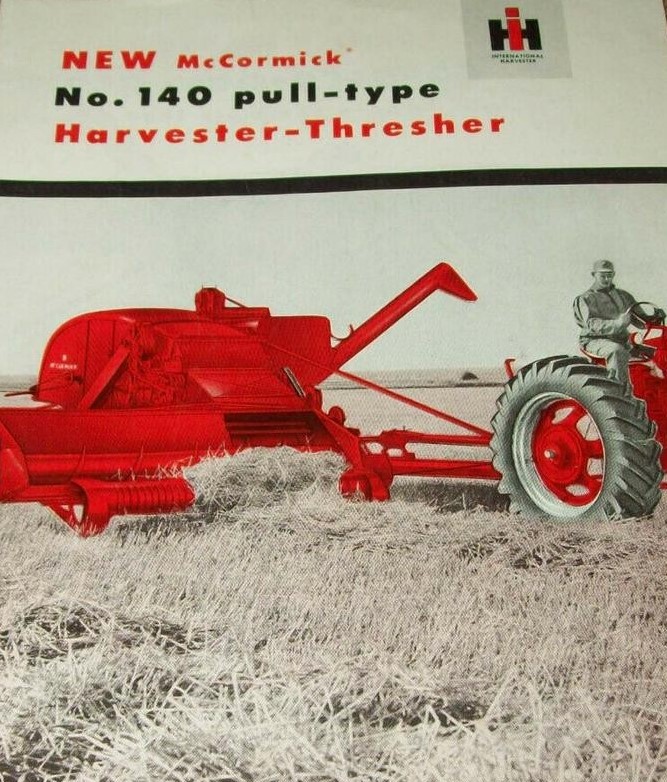

Photo courtesy of Wikiwand

The big labour saver to came along in the shape of a miniature harvester. This was the McCormick International Harvester – every bit of six foot wide at the cutter-bar and pulled along by a tractor. It was made to operate by the PTO of the tractor (Power Take Off). The cutter-bar was raised and lowered by the tractor hydraulics, and it discharged corn up a tube into the trailer. Quite a big saving in manpower and time.

As farming progressed along came the combine. What a great day! No more lifting large sacks of corn off the ground and onto a trailer.

Now if you pass a combine working, just stand and pity the men of the early days, those men who made farming what it is today. A modern combine has so many luxuries such as a 40ft cutter-bar, a computer to tell you if you are losing corn anywhere throughout the combine, how much acreage you have covered in a day, how much corn you have harvested, a two way radio link to the people you are working with, a radio to keep you amused in the day, a luxury sprung seat and air conditioning!

‘Jimmy’ in the 1950s would have thought he was in harvesting heaven!

Postscript

My dad (Pat) who wrote the above, had a favourite part of the harvest. It was when everything was safely in and the stubble could be burnt. He loves a good fire!

This particular year he had been making home-brew beer and, as was his custom, came home for his lunch (or ‘dinner’ if we are going to be accurate here) and made the addition of a pint of home-brew to go with his sandwiches.

The two fields behind our house were due to be burnt and he had only been gone for 20 minutes when the air was thick was smoke. Mum and I looked out of the window into a sea of flame. It seemed that the complete field was on fire and smoke billowed around the garden. The flames spread and there was no sign of Dad. Mum was getting really worried now. Both fields were ablaze and no sign of him.

We stood at the window, debating whether to call the fire-brigade and reluctant to do so as we knew who the fire-starter was, and waited. Slowly the flames died down. The smoke began to lift and breeze away and the blackened stubble was exposed. Still no sign of him.

Then mum spotted him. Slumped in the hedge, across the first field and in the shade of a tree, was Dad. Sound asleep.

The next day mum was in the village shop when another farmer said to her, ‘I saw Pat burnin’ yistdee, wos he got a fleerm thrower?’

Mum did not confess that he was tanked up on homebrew and dragging an oily, flaming rag behind him as he walked across the stubble…

The Airfield

I am lucky enough to live on the edge of Swannington airfield – only it is not actually in Swannington but Haveringland – and a bit of Brandiston. It was allegedly named Swannington as Haveringland Hall had played host to a number of high ranking Nazi’s between the wars and calling the new airfield by the next village along was thought to be cunning indeed.

Building began in 1942 by engineers from Ireland. One of these was my uncle Jack, who met and fell in love with my Auntie Joan. I like to imagine that perhaps the boot print in the concrete could have been his – but I expect not. Joan and Jack married and had five children.

The airfield opened in April 1944 and then Nos 85 and 157 Squadrons arrived with de Havilland Mosquito bomber support aircraft during the first week of May 1944. My grandparents lived just over a mile from the airfield with their seven children and at some point during the war, my grandfather began to help out at the airfield with a number of prisoners of war that were there. I’m sure it was not all sweetness and light by any means but my mother remembers how my grandfather would bring these young men back to his home, to share supper with the family and have a bit of normal life. Apparently Christmas 1944 was particularly memorable as grandad brought quite a few ‘prisoners’ home for Christmas lunch – one of whom had a squeezebox with him – and they had a wonderful time. My mother tells me that one boy wrote to my grandfather up until my grandfather died in the late 1970s.

My mother can remember having to help dress her younger siblings to stand on the gravel outside the Ratcatchers Inn as the air raid sirens had sounded. I hate to think of what my grandmother went through, trying to get seven children dressed and out of the door in the winter, knowing that my grandfather was on the airfield. There was an air raid shelter in a private garden nearby – but my mum’s family were not invited as there were too many of them…

With a prime target only one mile away it could not have been easy. Mum has said that she clearly remembers seeing and hearing a bomber crash on landing as it came back to the airfield and there were a number of fatalities at Haveringland.

I walk on there an awful lot as I live next to it and my windows look out across the runways. A major part of the airfield is on private land but there a lots of places to still stand on a little bit of runway.

My daughter and I were walking across there on the evening of VE Day during the first lockdown in 2020. It was a beautiful evening and the sun was going down. I remembered my mum telling me how she and her brothers and sisters were allowed come to the hanger on the airfield for a VE day party along with the rest of the people around here.

Molly and I stood on the edge of the runway, looking across to the technical buildings that still stood. The air was warm and there was not a sound but the breeze, but we both felt that if we were to walk around the hedge and step across to the hanger, there they would all be. My grandparents with their children, Auntie Joan and her handsome Irishman, Auntie Betty and Auntie Hazel dancing away… all having a once-in-a-lifetime party.

It is a landscape that is full of echoes. Standing on the runway looking north, you would still see the same view that the pilot sitting high above his twin Merlin engines would see from his Mosquito. In front of you is the church of St Nicholas in Brandiston, to the right is the church of St Peter in Haveringland, behind you would have been a hanger – the footprint of which shows up as a crop mark in the right conditions – and to the left is the machine gun and cannon range. First one engine would start and then the second. The roar would become a scream and you would thunder down the runway to take off between St Nicholas Church and the technical area. Straight up and over Cawston and then bank right and head to the coast.

Coming back you could use the east/west runway and come to the left of your pals who were billeted at Haveringland Hall and touch down a few metres past Haveringland church on your right. The present Norwich – Cawston road runs along this part of the airfield near the east/west runway but this was diverted during the war.

The east/west runway is now down to a third of its width but the poplars, planted by my dad and the farmer in the 1950s, still have a gap for the full width of the runway.

The past is tangible out here and the air heavy with reverberations. I am a little obsessed with it but I feel it should not be forgotten, nor the people who built it and worked there. Nature is reclaiming parts of it and that is only right. Where the cannon range stood there are now thistles and sugar beet grows unevenly on the where the ghosts of the spectacle loops are. But it is all still there in a way and some of them never left to go home again.

Life on a Norfolk Farm in the 50s

Pat Waby writes about life on a farm in the 50s:

I was introduced to Norfolk farm life in 1958, perhaps somebody should have told me hard skin on the hands was a great help. My hands to say the least, were debatable. Two years in an office and five years in a military band was hardly a good training to top a frozen sugarbeet and throw it in a continuous motion onto a cart for eight hours every day.

Compare today with then! Four men chopping beet by hand would probably clear half an acre – today, two men on a six row lifting machine with one tipping trailer will remove twenty acres each day.

The farm worked in the fifties was a very tough person. A sack of oats would weigh twelve stone, barley would be sixteen stone, wheat would be eighteen stone, and the only way to move them from A to B was by muscle power. Today a single blowing machine will load a lorry in twenty minutes.

A tractor driver in the fifties had no cab. He would sit on a sack for comfort on his iron seat, wrapped in an army overcoat with a corn sack over his knees. When he alighted from his tractor he would quite easily fall down because he had no feeling in his knees. Eight hours each day rain or shine!

A modern tractor has air conditioning, a wireless, a computer, a two-way radio and cushioned sprung seat – and more.

What would ‘Old Jimmy’ say in the fifties if you explain the above to him, and do you think you would ever get through to him that a tractor with a six furrow plough would come out of a shed and plough from side of a field to the other and not even have a driver. Progress!